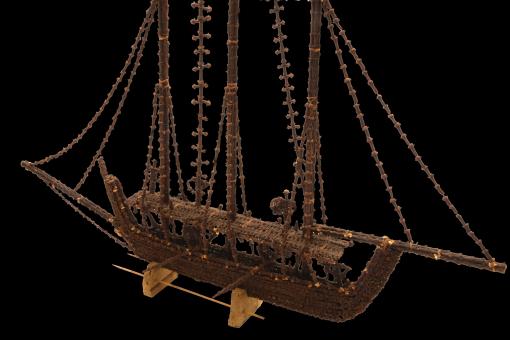

The geographer Yi-Fu Tuan in 1977 suggested that a museum ‘consists wholly of displaced objects’ where the only thing objects have in common is that they were not designed to be in a museum in the first place. How have objects come to be in our collections? Where have they been before? Often museum labels tell us specific details about the object, who made it and when, but remain silent on its movements before entering the museum. Some objects travel extensively, including across national borders, creating new meanings along the way. Built in 1625 for the Portuguese, the Si Jagur canon travelled from Macau to Malacca to Batavia (present day Jakarta). It has since been in the collection of three different museums in the city. The stone portico from the shipwreck of Batavia is another example of a well-travelled object. Originating in Germany, it was intended to serve as a gateway to Jakarta’s Dutch port, but ended up lost on a reef in the Indian Ocean. Now, over 300 years later, it resides in a regional museum in Western Australia where its significance is framed by its Dutch connections. This object presents an opportunity to not only explore the colonial legacies shared by Indonesia and Australia, but is also a ‘gateway’ for new Indonesian perspectives on well-established European narratives.

Other objects reflect stories and ideas that travel, such as the Yirrkala batik, an interpretation of bark paintings made by an artist named Ronald Nawurapu Wununmurra. It is inspired by the Yolngu traditional songs which tell the story of Makassar (Bugis) sailors visiting Arnhem Land. Similarly, the Chinese coins in the collection of Old Banten Archaeological Site Museum unearthed during an archaeological dig illustrate the importance of Banten as an important trade hub since the 7th century CE and continuing transnational connections.