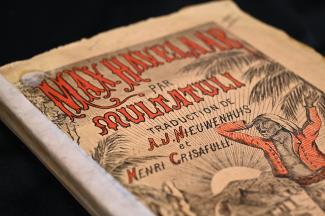

Museums and galleries have a long history as part of colonial practices. This includes collecting and displaying objects from colonised countries, in creating and reproducing histories or world views that privilege colonial powers and control Indigenous cultural heritage. However, collecting institutions are increasingly recognising the legacy of their colonial beginnings and are now engaging with source communities to ensure processes of self-representation, self-determination and shared responsibilities. Many nation-states use heritage sites and museums to make expressions of contrition, regret, and apology. One aspect of this is rethinking how objects are used to tell stories that might redress the wrongs of the past. However, even objects that might appear to have a positive story to tell can be more complicated than they first appear. One such object is the first edition of the novel Max Havelaar, by Eduard Douwes Dekker.

A colonial administrator with a conscience

Born in Amsterdam in 1820, Dekker was a colonial administrator who worked in what was then the Dutch East Indies. His colonial career was plagued by scandal, but he rose steadily through the ranks to become Assistant Resident in Lebak, in what is now the Banten province in Indonesia. He became increasingly disturbed by the abuses of the colonial system and openly protested against the treatment of Javanese agricultural workers. Threatened with dismissal, he resigned and returned to the Netherlands where he wrote newspaper articles and pamphlets to expose the cruelty of Dutch colonial rule.

His most famous work is the novel Max Havelaar: or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company (translated from the Dutch Max Havelaar, of the Koffiveilingen der Nederlandsche Handelmaatschappy) which he wrote under the pseudonym ‘Multatuli’. The book exposed the brutality of the forced cultivation system in Java. Published in 1859, it had an immediate impact in the Netherlands. Its account of Dutch colonial policy ‘sent a shiver through the Dutch nation’ (Van Neil 1991) and shamed the Dutch colonial government into changing its approach to colonial administration in the region through what was known as the ‘Ethical Policy’.

The Western Australian connection

Dekker’s book was widely translated, including into French, Russian, Italian, and English and read in many parts of the world. Its influence extended to the Russian revolutionary, Lenin, who used it to illustrate the evils of colonialism. There is also a direct connection to Australia through the 1927 English edition which was translated by William Siebenhaar, a Dutch anarchist who fled to Western Australia in 1891. The preface to Siebenhaar’s translation was written by the famous English novelist D. H. Lawrence, whom Siebenhaar had met in Western Australia in 1922. The reception of the 1927 translation was positive, and A. Street writing in the Australian Worker described it as

poetry, satire, statistics, a love-story, actually a murder-mystery, all- served up in Dutch fashion into a rare and complicated dish, spiced with all the Indies. Open the book; anywhere and begin to read; you cannot put it-down.

Although Street took pains to point out that the book had little relevance to contemporary times.

Siebenhaar also translated Jan Jansz's account of the 1629 Batavia shipwreck and mutiny on the Western Australian coast – Ongeluckige Voyagie, which was published in 1647 – as The Abrolhos Tragedy, in The Western Mail in 1897.

Despite some claiming that the book ‘killed colonialism’, other commentators suggest the story is more complex. Dekker wanted to improve the conditions of the Javanese rather than wanting to end Dutch colonial rule in the region. Regardless of the author’s intentions, Max Havelaar was an inspiration for others to fight for justice.